Without someone having an opinion!

without someone having an opinion!

You may come across this in the /readme folder or maybe from the /open_tabs folder about ‘Ballerina Farm’. Since I have no idea what context you are bringing with you, I will give a little.

This post comes from two distinct thoughts I have had over the last week.

- Paige Desorbo on the podcast ‘Giggle Squad’ said something incredibly real and honest:

“I am so over the narrative that men can do whatever they want at any age and women can’t do what ever they want at any age” -Paige Desorbo, Giggly Squad

She was performing for the gigglers in that moment, so succinctness was never the goal. With that in mind, I present the refined version:

Men are free to do anything at any age; women are denied that same freedom at every age. - The rise of the “trad wife” lifestyle seems to raise the question:

Is this way of life setting feminism back?

Which leads to the broader question I keep circling back to.

Why can’t women do anything without someone having an opinion about it?

I don’t have a tidy answer, mostly because “it’s all men’s fault” isn’t serious analysis and “women should fix it” is the exact problem I’m talking about. The point of this post is to stop defaulting to women as the solution, especially when they are already being asked to do more than men at every stage.

(I sit here watching the cursor blinking at me, begging me, pleading with me. Say something profound…say something meaningful…say something that fixes the age-old problem that women are not seen the same as men in the eyes of the world.)

Women are not the same as men, but equality was never meant to require sameness. Confusing the two may be the root of the problem.

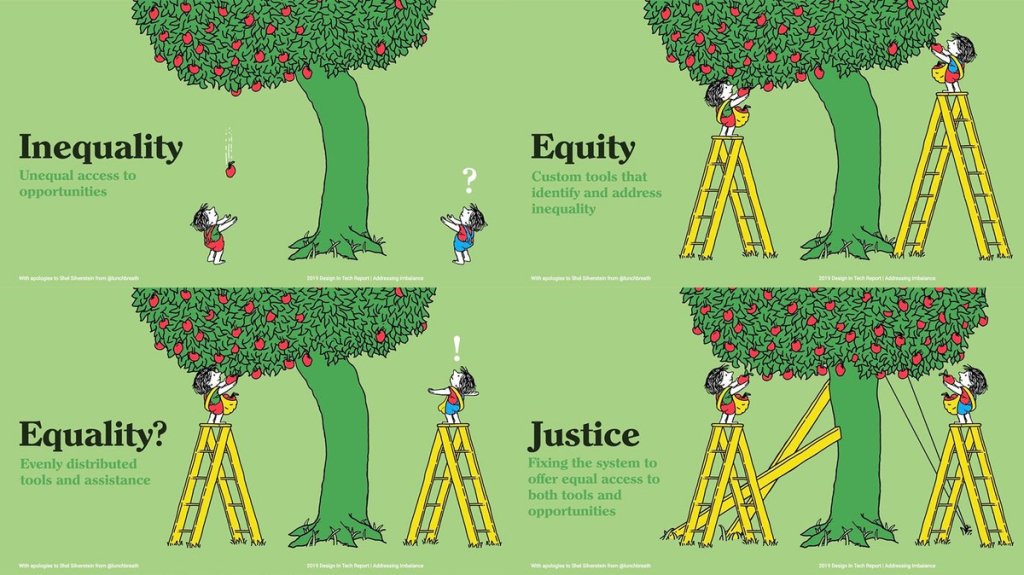

Equality is not a product of sameness. What we are often actually arguing for is equity. Equality does not require identical lives, but equal outcomes are impossible when everyone starts from different footing. So perhaps the work is not insisting on equality at all, but recognizing that equity is what is required.

That recognition, however, demands we move past an obsession with victimhood and confront a quieter truth. Some people are dealt all the right cards. Others are handed a piece of paper with a spade drawn on it and told it is the same as the bicycle card everyone else is holding.

To promote equity, you have to be comfortable with the idea that having the upper hand in life should not automatically guarantee success.

I acknowledge this is not a simple, uncomplicated ask. It is uncomfortable to sit with. Like a tag in your clothes that you would prefer rip out than have to deal with the continued itchiness that comes with it.

It asks us to look honestly at where we stand, and to acknowledge the ground beneath us may be more stable than the ground beneath someone else.

Our instinct is often to turn inward and assign blame.

Feel guilt?

Explain ourselves?

Dismiss the idea all together?

“Why would anyone blame themselves for the good cards they were dealt, when no one is blamed for the bad ones?” – you to you

Understanding equity is not about guilt, and it is not a call to self-punishment. There is not a requirement for anyone to fix everything for everyone. That expectation is unrealistic, unsustainable, and unfair in its own right. Equity is not a savior narrative. It is an acknowledgement that different starting points exist, and pretending otherwise…

serves no one.

So maybe this is where this thought stays for now. Unfinished & Unrefined. Something to return to later, once I have lived a little longer and have a bit more perspective to offer.

Which brings us back to women.

Because for women, the gap between equality and equity is not abstract. It shows up in expectations that are invisible until you trip right over them. Women are told the playing field is level while being asked to perform the labors of life.

Emotional Labor

Reproductive Labor

Social Labor

Domestic Labor

Aesthetic Labor

Relational Labor

Professional Labor

Caregiving Labor

an ambitious list to read. an ambitious list to live.

This is happening alongside measurable progress.

As documented by the National Center for Education Statistics, “over the past two decades, women have made substantial educational progress. The large gaps between the education levels of women and men that were evident in the early 1970s have essentially disappeared for the younger generation” (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 1996, p. 1). Women have not only closed the gap but have surpassed men in higher education enrollment in the decades since. These are not marginal shifts. They are structural ones.

Women are also increasingly the economic backbone of their households. A 2023 analysis by the Center for American Progress, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, found that “45 percent of mothers were the economic backbone of their families, bringing in the bulk of the earned income for their households” (Andara, Estep, & Salas-Betsch, 2023). Nearly half. This is not symbolic progress. This is material responsibility.

Yet the expectations have not loosened. They have multiplied.

When women succeed professionally, they are still expected to carry the majority of the domestic and caregiving labor.

And when they don’t, or when they delay or opt out of motherhood altogether, they are asked to justify that decision.

Women who choose to have children “later in life” (an arbitrarily ominous label rarely applied to men) are reminded of everything they are supposedly giving up.

Women who have children “too young” are reminded of those who came before them, as if gratitude should substitute for autonomy.

And women who do both, pursue careers and raise children, are left navigating a constant state of contradiction.

“You look tired.”

“Have you thought about putting more effort into your appearance?”

“Are you sure that outfit is appropriate for this role?”

“You aren’t nurturing enough.”

“You’re too focused on your career.”

“You want to be treated as equal, yet you’re asking for flexibility?”

“Why aren’t you married yet?”

“Why did you get married so young?”

“Why don’t you want children?”

“Why did you wait so long to have them?”

“Why would you have children now?”

“If you are here, who is watching the kids?”

“Are you sure you can handle all of this?”

These contradictions are not accidental. They are the residue of a system that expanded access without recalibrating its expectations. Women are required to meet standards historically designed for men, while simultaneously being asked to justify their presence and choices within those same structures.

Men are not subjected to the same scrutiny.

No one asks men:

“Have you thought about your appearance?”

“Are you worried that outfit makes you look less credible?”

“Do you think looking tired undermines your authority?”

“If you are here, who is watching the kids?”

“Are you concerned this choice will hurt your career long term?”

Instead, men are granted narrative freedom. Their ambition is assumed to be neutral. Their authority is presumed intact. Their personal choices are treated as incidental rather than disqualifying. Women, by contrast, are often told that being allowed into the room represents equality itself, as if access alone resolves imbalance. What goes unacknowledged is that entry comes with conditions.

For a woman to succeed, she is expected to perform according to norms historically shaped around male lives and male freedoms. Yet when she adopts those norms, prioritizing career, asserting authority, demanding flexibility, she is penalized for deviating from femininity. Men are allowed to move through the world unencumbered by this contradiction. Women are not, not through any failure of their own, but because their legitimacy is still filtered through perception rather than performance, judged on the basis of sex rather than substance.

Historically, women were denied financial autonomy outright. No-fault divorce laws only became widespread in the United States in the 1970s. Women were not legally guaranteed the right to open a bank account or obtain credit without a male co-signer until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974. These constraints did not disappear quietly. They shaped behavior, dependency, and risk tolerance across generations.

So when women today are told they are starting from the same place, the statement is functionally incomplete.

The ground may now be legally level, though even that remains contested, but the weight women are expected to carry on that ground has not been redistributed.And when women choose different, the scrutiny intensifies.

A woman who opts into “tradition” is read the referendum of feminism.

A woman who opts out is accused of rejecting it.

A woman who wants both is unrealistic.

A woman who wants neither is selfish.

The critiques contradict each other, which makes it clear that the issue is not the choice itself.

Her choices are not allowed to exist on their own terms.

Her choices are treated as symbols, signals, and warnings.

Men are afforded this narrative of neutrality.

A man changing paths is exploring.

A man opting out is reassessing.

A man choosing “tradition” is stable.

A man rejecting it is progressive.

A mans decisions are treated as individual preference rather than a cultural commentary.

Their lives are allowed to be personal.

So we end up right where we started.

Women can choose anything, so long as they are prepared to defend it. Their lives remaining open for commentary, a public performance with critics ready to weigh in.

This is why the rise of the “trad wife” sparks panic, why career-first women are warned about time running out, why mothers and non-mothers are interrogated, and why women who attempt to hold multiple identities at once are treated as contradictions rather than people.

This is not because women are doing something wrong. It is because women are doing many things at once. Carrying expectations that were never renegotiated when the doors finally opened.

And maybe that is the quiet truth underneath all of this. Progress has given women access, education, and responsibility, but it has not given them narrative freedom.

Women have been allowed into the room, but they are still expected to perform once inside it.

This is not a call for women to choose better, louder, softer, or more strategically. It is not a demand for men to fix everything, or that anyone carry guilt for the hand they were dealt.

The question is not whether women are choosing correctly, representing progress appropriately or doing enough.

The question is why women are still being asked to explain themselves at all?

Equality does not require women to become more like men. It asks of us, all of us, to allow difference without penalty. Until that distinction is accepted, women will continue to be measured not by their outcomes, but by how well their choices conform to someone else’s expectations.

Perhaps equity, in this context, looks less like fixing women and more like acknowledging the full scope of who they are and what they are already carrying. and then, quietly, getting out of their way.

Image Sourced From: https://ywcaspokane.org/2023-racial-justice-challenge-equity-vs-equality/

TL;DR:

Women have made real, measurable progress in education, income, and autonomy, but expectations have not adjusted to match that progress. Women are still asked to justify every life choice, while men are largely allowed narrative neutrality. This is not about blaming men or fixing women. It is about recognizing that equality without equity, and access without freedom from scrutiny, is incomplete. Women don’t need permission or prescriptions. They need space to live without constant commentary.

References

National Center for Education Statistics. (1996). The Educational Progress of Women (NCES 96-768). U.S. Department of Education.

https://nces.ed.gov/pubs96/96768.pdf

Andara, K., Estep, S., & Salas-Betsch, I. (2023). Breadwinning women are a lifeline for their families and the economy. Center for American Progress.

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/breadwinning-women-are-a-lifeline-for-their-families-and-the-economy/

Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1691 et seq. (1974). U.S. Department of Justice – Civil Rights Division. Retrieved January 2, 2025, from https://www.justice.gov/crt/equal-credit-opportunity-act-3

Leave a comment